About the Interviews

It is fair to say that interviewing elderly Cypriots has been quite an education for me. I have discovered many things about Cyprus-past that I simply didn’t know before. As a Greek Cypriot-Australian born to migrant parents, I have had a long-distance and somewhat limited appreciation of my cultural heritage and ethnic roots. Tales of Cyprus has changed all of that. I now feel reconnected to my heritage. Even my Greek language skills have improved!

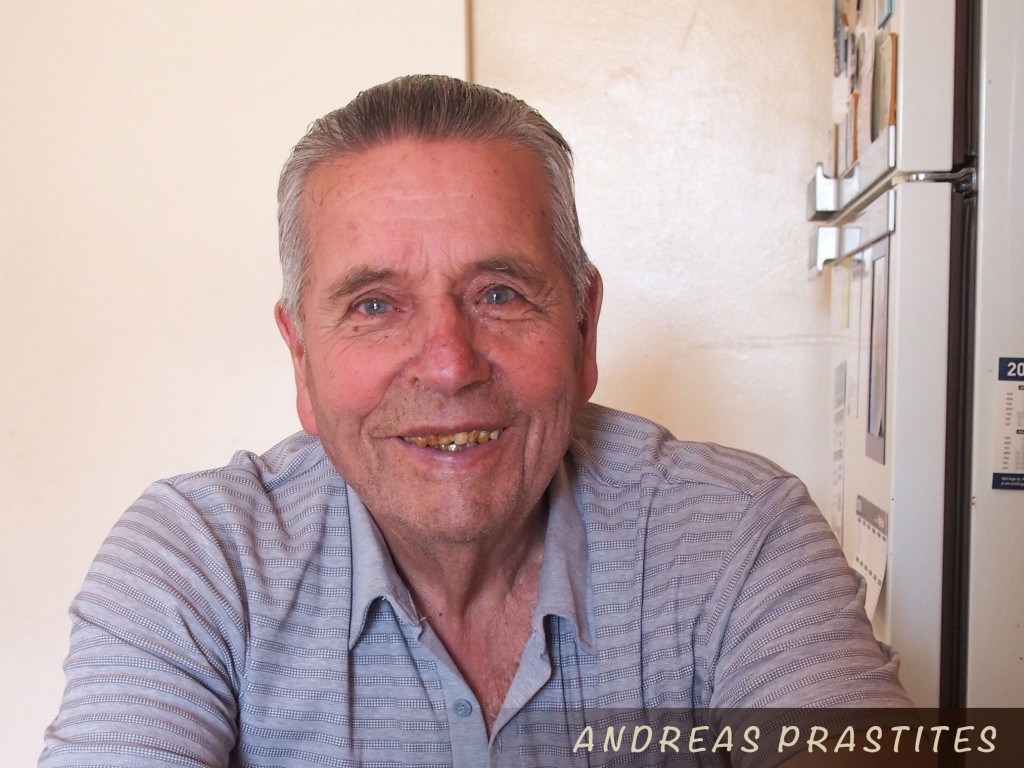

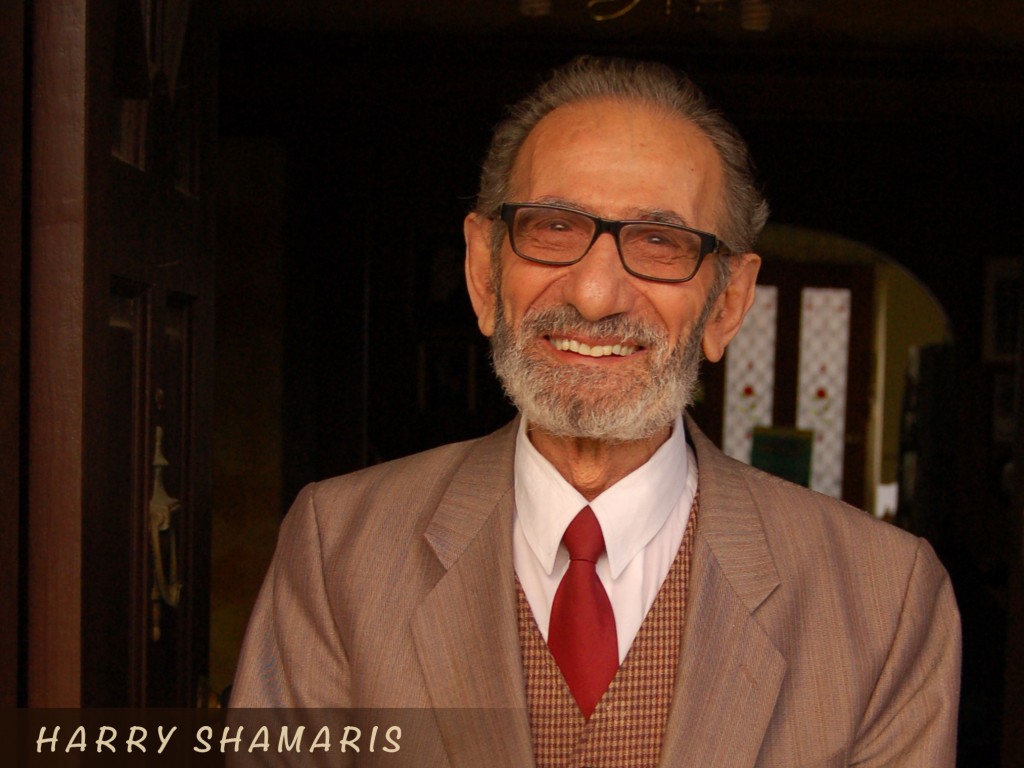

The people I chose to interview for Tales of Cyprus were mostly aged between eighty and ninety-five, born between 1920 and 1940. Many of them left Cyprus in the 1950s to start a new life in faraway places such as the United Kingdom, America, Canada, South Africa and Australia.

Many common topics and themes emerged during the course of my interviews. For instance, the severe poverty that existed at that time; the dependency on child labour; the lack of education; the value of eating what you grew; the unconditional respect for parents and village elders; the prevalence of arranged marriages; traditional gender roles – and of course, migration.

Nearly all the people I interviewed stated that although they were poor and suffered many hardships – they were ultimately content. By appreciating the little that they had, they reinforced the popular old adage that ‘less is more’.

Through these interviews I was also able to confirm that Muslims and Christians on the island were friends and coexisted in peace. In fact, all the people that feature in this book spoke of endearing and loving friendships with all Cypriots regardless of their religious beliefs. They stated that apart from language and religion there were no cultural differences. “We even looked the same,” was how one person put it.

Conducting these interviews has had its fair share of challenges. Firstly, I had to establish trust and credibility with my target group. To this end, I had prepared legitimate and clear answers to the question most often asked, which was: “Why are you doing this?”

I had to ensure that the people I interviewed knew that my desire to record their stories was honourable and that my primary objective was to record the truth about their past.

This was difficult, because recording objective truths is not a familiar pursuit and not widely understood by many subsequent generations, even in Cyprus.

Understandably, some people were sceptical about this project and indeed my intentions. Others appeared apathetic. Having a website and a Facebook page has been an effective way to communicate my message and lower some of the barriers. I also went to the trouble of designing information flyers and brochures in Greek, English and Turkish to reach more people.

Once I explained that my primary objective was to document the sacrifices made by past generations, most people were more than happy to talk to me.

I had to be patient, and this was very difficult, knowing that my target group was getting older and frailer. Sadly, many elderly Cypriots died while I was waiting for the final approval to interview them. Remarkably I was able to conduct nearly all my interviews face to face. I did this for two simple reasons. Firstly, I believe that people feel more relaxed in their home setting, allowing their stories to flow more freely. Secondly, using the Internet or even the telephone would have made the interview static and impersonal thus creating a feeling of detachment. Most of my interviews were conducted in Melbourne, London and Cyprus.

Once I had established trust within the community, I had to ensure I could gather enough information to write an accurate and informative life story. My questions were deliberately phrased to avoid ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers. I had to become skilled in the art or prompting and probing for more information. My teaching background had prepared me wonderfully for this kind of challenge.

The idea of recording one’s history seemed strange and pointless to some people. “Why do you want to know about my past?” was a common response. “Who cares about my story; who would want to read about my life?” Perhaps you could argue that a lack of education meant that older Cypriots did not appreciate or value the documented memoir.

On the contrary, I would suggest that many older Cypriots perhaps felt a sense of shame or even remorse about their past lives. Given that most had suffered great hardships and witnessed abject poverty, perhaps the memory of walking barefoot and hungry in a village full of basic mudbrick homes was not worth mentioning, let alone recording in print.

I quickly realised as I conducted each interview that I was dealing with an oral, word-of-mouth society. With perhaps one or two exceptions, most people did not have any written accounts of their life story. There were no personal diaries, no letters, no transcripts from school, or work references, or travel documents. There were no certificates regarding property and marriage. Even the few photographs they had kept had no clues written on the back. For this reason, recalling the names of the people in the photographs and the dates and locations was quite an ordeal.

One of the most tragic confessions I often heard from older Cypriots was how all their personal documents and photographs were either lost, destroyed or deliberately thrown away by other family members. Others lamented that many of their treasured possessions were left behind and abandoned when they were forced to flee their homes during the troubles that engulfed the island in the 1960s and 1970s.

Given the advanced age of my target group, it was no surprise that many older Cypriots had difficulties remembering specific details and facts about their past such as the names of friends and relatives, the name of their school or the name of the migrant ship they travelled on. In some cases, the onset of dementia had started to diminish the clarity of their recollections. I have always known that this project would be a race against time and at a certain point, it seemed that patience was a virtue I could no longer afford. I had to act fast and I had to extend myself in ways that made it possible for me to capture someone’s story before it was too late.

While I cannot claim that the stories in this book state the complete historical truth, they are the reminiscences of my subjects. Sometimes it would be obvious during an interview that a person had made an error. For instance, it is very unlikely that someone might have earned five pounds a week in 1941 working as a waiter in Kyrenia, as they may claim. From my extensive research, it is much more likely they were paid around two shillings a week. I am also sure that some stories have been exaggerated.

But do these minor details matter? All I hoped to achieve in this book was a faithful translation of each interview that would then serve as an eyewitness account of the past. In other words, a recollection of a bygone era as told by those who were there.

Tales of Cyprus is, at its heart, a collection of oral histories based on the living memories of a very special generation. Who am I to question or even doubt their stories. I am extremely grateful to have had the privilege of recording their memories in this book. They speak of a time of strength and resilience in the face of extreme adversity. A time when the debt collectors loomed large in people’s lives; a time when the vagaries of weather could ruin crops and destroy one’s livelihood.

I was also very fortunate to have had the help of many people in the cross-referencing and checking of certain facts, and none more so than the living descendants of the people I interviewed. Sometimes key dates were disputed, or certain names and places, and it was the descendants of my subjects who would help sort through these details. Despite this help, I would often go back to a person’s house two or three times to tidy up details and close any gaps in a story. In more than one case, the same story would be retold differently the second time, offering strange new facts and information. The fallibility of memory is something I am, more than ever, fully aware of when interviewing an ageing population.

Sometimes during the course of an interview a family secret was revealed which surprised the descendants and family of my subjects. This is a most remarkable outcome for Tales of Cyprus. For instance, it was only after I interviewed my mother’s sister that I discovered that my mother was in fact engaged to another man before she met my father. Similarly, when I interviewed my father’s brother, I discovered that before my father had left Cyprus for Australia, where he married my mother, he had been in love with a Catholic girl. My parents never mentioned these relationships to me.

Then there are those memories that are just too painful to share. I was often taken into the confidence of my subjects and told personal stories that they did not want repeated or written down. In these cases an interview suddenly turns into a confession. I have heard some incredible things over the years, but I have been made to promise not to share them with anyone, not even with the person’s immediate family. There have been stories told that are so fantastic and so unbelievable that it makes me wonder, what else do people keep to themselves and eventually take to their grave.

Even in my own family, I was told about a murder that was committed in my maternal grandmother’s village of Arsos over a hundred years ago. Would you believe that even after all these years I still have trouble getting straight answers from some of my relatives?

Some people refused to be interviewed in case they said something that may offend a living relative. “What if someone reads what I have said about their grandfather?” I was once told. Some of the best stories I have heard cannot be published in accordance with the wishes of the storyteller.

And on the other hand, there are also those people who will tell you everything about their life and pour their hearts out during an interview. “Go ahead!” they tell me. “Write it all down. People need to know what happened to me. People need to know the truth.” I once interviewed a ninety year old man who confessed openly that he visited brothels frequently in his youth. His family agreed to have this information published – purely to show how the strict moral code at the time forced many men to visit brothels rather than approaching or dishonouring the reputation of a girl from their village.

With all my interviews I deliberately focused on investigating life on the island as it existed between 1920 and 1950. I was not interested in peoples’ individual opinions about the political turmoil that has engulfed Cyprus since the 1950s. I know that I upset people when I refer to the first half of the twentieth century as the golden era for Cyprus. “How can you say that, Costas?” they respond firmly. “Are you forgetting the poverty, the debt and the lack of jobs?” I tell them that according to all the people I have interviewed for Tales of Cyprus, they all tell me that life at this time was pretty good, despite all the challenges they faced. Furthermore, they remember their youth with great fondness, joy and longing.

After so many interviews I have come to appreciate that my parents’ generation lived a humble life without any airs or graces. They had fears and concerns just like the rest of us, except that their fears and concerns were based on simple truths and practical matters such as making sure they had enough food to eat and staying alive long enough to get married and start a family. They weren’t distracted by the consumption of goods, material gains and selfishness – in the way that so many of us are today. For me, there have been great losses in the transformation from a self-contained, self-sufficient rural society to a largely fragmented urban existence. We have lost our sense of community which was the heart of life in Cyprus at this time.

Tales of Cyprus has been a fantastic education for me, serving up many invaluable lessons on how I should live my life. I hope you too are as enthralled and enchanted by the life stories in this book and perhaps learn a thing or two about the way Cyprus used to be.